When I was a Junior in high school my history teacher gave us students an assignment to interview someone who had lived through World War II. We could gather information from a veteran, a civilian, anyone who could remember those six years of war. The closest person to me would have been my father. Despite our good relationship I knew very little about his life before he emigrated from Europe. I knew he ended up in Germany at the end of the war, but that was it. He had never offered details, so I had never asked him about it before.

“So Dad, I need to interview someone who lived during World War II for a class assignment. Would you be willing to help?”

He hesitated for a moment. “Sure, I’ll help. What do you need to know?”

“I’m not sure, my teacher didn’t give us any specifics. Why don’t we start with where you were living at that time.”

“The first few years of the war I lived in my village of Rzeplin.”

“Where is that in Ukraine?”

“It’s not. It’s in Poland.”

I was confused. “But we’re Ukrainians – what are you talking about?”

“At the time I was born, my village and your mother’s village were under Polish rule, but we were Ukrainian by heritage. Once the war began, the Soviets took over our area but two years later in 1941 the Germans invaded.”

Holy crap! “So…your area was ruled by three different states in six years…”

“The last three or four years of the war, I was all over Europe.”

“Why was that?”

“Mostly because I was trying not to get killed.”

“By the Nazis?”

“By the Soviet army, by the Nazis, by idiots who just wanted to shoot at anybody.”

I had to take a moment to wrap my head around this information. I could see why he had never voluntarily brought up his life in Europe but at that moment he seemed almost eager to discuss it. Years of private thoughts and secrets were unleashed, situations he had always thought best to just try to forget.

My dad started out by giving me some historical background. “By the early 1940s, Ukrainians had been through enough of Stalin’s evil. Forced starvation of millions in the early 1930s (Holodomor) and later that decade, any person showing signs of Ukrainian nationalism was sent to hard labor or shot. In 1941 when Germans invaded Russian territory, your mother’s and my villages were in the middle of the war zone. Our villages were fairly secluded, but by 1941 there was no way to escape either being drafted or brought into labor. Your mother and I were teenagers, very strong and able. For us Ukrainians, we all felt the Nazis came to liberate us and many of them willingly left with them.”

This shocked me. “But…why…how?”

“Propaganda. Many Ukrainians had suffered under Stalin and the Nazis had promised them prosperity by coming to Germany to work in their farms and industry. They knew how Stalin had treated us, though I’m sure they didn’t care. Ukrainians were eager to leave the war zone and with the promise of getting paid it was a better situation. We had no idea in our remote villages as to the horror of Nazi Germany. No TV, some radio, but it was all Soviet sponsored. Even a newspaper was rare.”

“So…what did you do?”

“My own mother had just died, my sister had married and was starting her family, my brother was still a young teenager and our father – well, he pretty much drowned his sorrows after my mother’s death and we had to fend for ourselves. I ended up taking my Uncle Yakiv’s advice to travel as far north as Estonia to work in a factory he knew of. Eventually, I was drafted by the German army. Fortunately for me I wasn’t put in combat. I was ordered to be a guard. That all ended when I arrived at Dachau.”

“Dachau? You mean the concentration camp, Dachau?!”

“Unfortunately, yes.”

I could tell you the rest of the story, but I’ll save it for the stage production, Borderland.

Through reading and research I learned my parents were known as Ostarbeiter – Easterners, Slavic people. They were initially paid for their work, a small amount they could only spend where they worked on essentials, but ultimately they became forced laborers. Just like the Jewish people, forced laborers from eastern Europe required to wear a patch on their clothing that marked them – OST. They were also classified by the Nazis as another group of Untermensch or, sub-humans.

Sub-humans. Let that sink in.

We only need to turn on our TV or check the internet these days to realize there are some in this country who believe others living here are sub-human. We’re bombarded by propaganda that does exactly what the Nazis did – cater to our most vulnerable areas, placing blame on others for things we find to be unfair to us. We’ve seen people carry symbols of oppression over the past few days with no remorse. People no longer hide behind hoods to call others sub-human. Many of us were incensed by the ugliness of the attitudes of those who carried Nazi and Confederate flags and tiki torches and of a president who won’t denounce the evil actions and rhetoric of those who openly denigrate Jews, Muslims, people of color, women, or those who don’t identify themselves as cis white males. I had to ask myself: When do I look at people and think of them as “sub-human”? How much am I to blame for systemic bigotry, partisan vitriol, divisive language, choosing hatred over empathy? What sort of propaganda do I buy into and how do I shut my eyes to injustice?

My parents witnessed and experienced the worst of what humans are capable of. Consequently, they kept themselves informed by watching the daily news, reading the newspaper, subscribing to news magazines, and participated in healthy debate to be sure they could make informative decisions when voting and living in a country that gave them so much freedom. As we have come to find out these days, there is a barrage of media that contradicts each other. Now more than ever we need to use critical thinking and if we feel things are not “normal” we need to call things out for what they are. One thousand white men in Charlottesville – and a handful of women – bought into bigoted propaganda and now three people are dead because of it. Between 1932-1945 it’s estimated ten million Ukrainians died due to killing policies brought on by propaganda, some of them included in the six million Jews that died as well.

My parents didn’t have a whole lot of choices in the midst of World War II due to state-sponsored oppression. Some in their situation retaliated in kind, became complicit in war crimes. Why my parents had the moral compass not to comply can only be defined by grace. All it takes is one good or one bad choice to change the course of a person’s ethical character.

These words can’t be stressed enough: Choose Wisely.

My father’s official Ostarbeiter photo

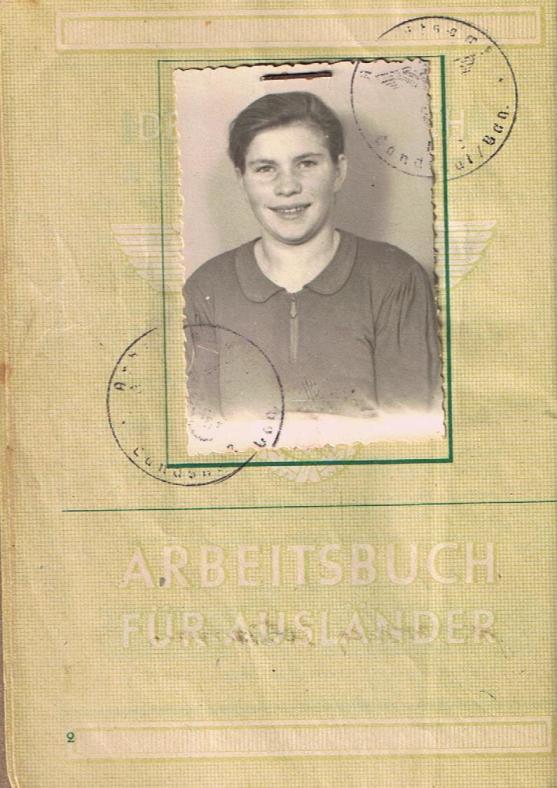

My mother’s official Ostarbeiter photo

Entrance to Dachau Concentration Camp – “Work Means Freedom”

Tags: history, propaganda, research, Risk

Beautifully written, Nat! You share another chapter of your parents lives that I didn’t know. They lived in honor and survived so many unimaginable things. Thank you…looking forward to the play!! Love you!

I want to read the book and see the play. So much of my own history my grandparents never talked about.My grandmother always cried when we asked about Poland.Which she referred to as the old country.